Comprehensive Guide to Protecting Florida’s Underground Water Resources

Table of Contents

Section 1. Understanding Florida’s Groundwater Classification System

1.1 Purpose of Classification

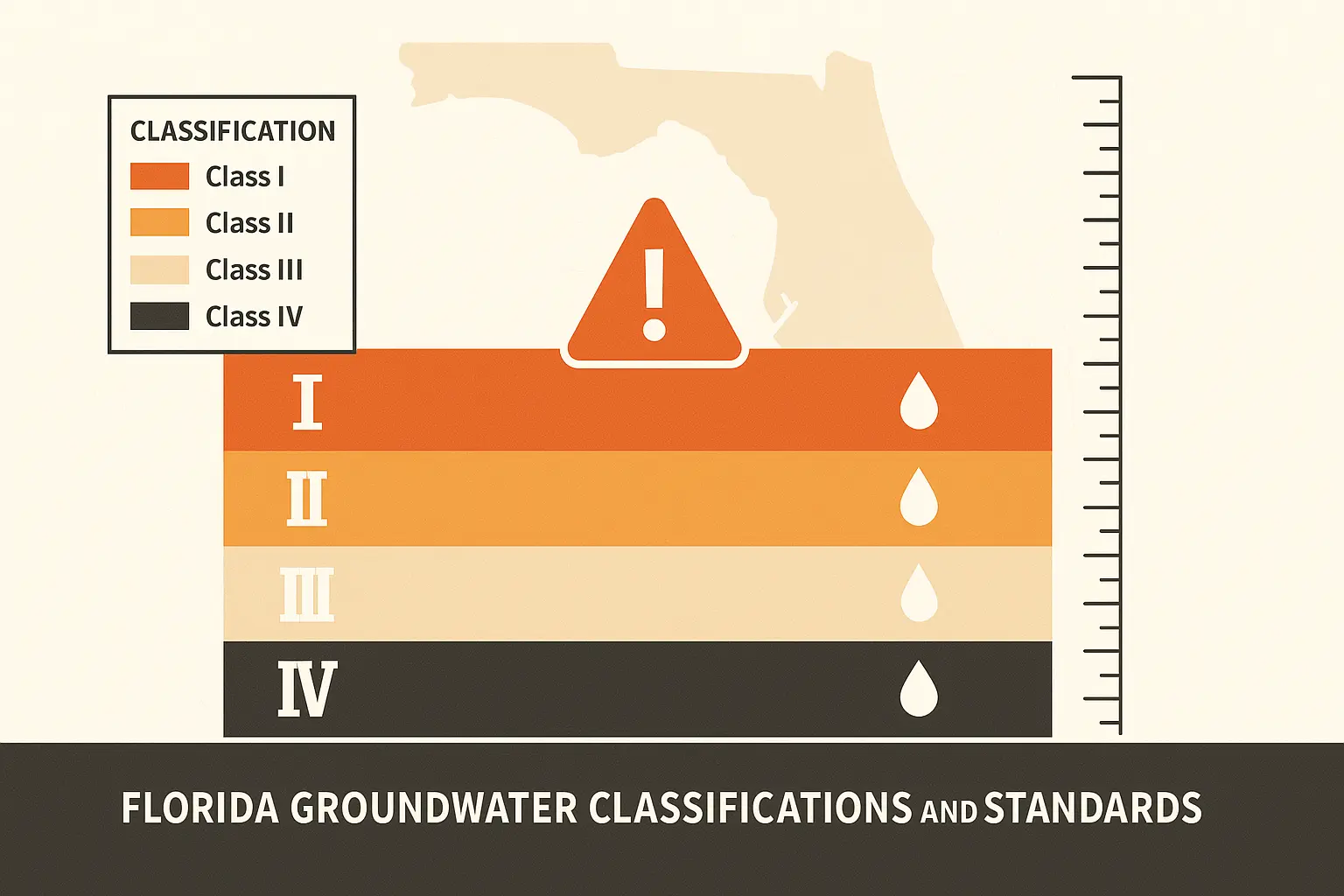

Florida’s groundwater classification system divides all underground water into distinct categories based on quality, current use, and potential for future use. This system, established under Rule 62-520.410, F.A.C., creates a hierarchy of protection that ensures the most valuable water resources receive the strongest safeguards while allowing appropriate use of lower-quality waters.

The classification system serves multiple purposes. It directs limited regulatory resources toward protecting the most critical water supplies. It provides clarity for permit applicants about which standards apply to their discharges. It allows flexibility in managing waters that have no drinking water potential while maintaining strict protection for current and future drinking water sources.

1.2 The Five Classification Categories

Florida recognizes five distinct groundwater classifications, each with its own protection level and standards. These classifications range from the highly protected F-I and G-I single source aquifers to the minimally regulated G-IV deep saline aquifers.

Understanding which classification applies to your site is the critical first step in any permitting process. The classification determines which water quality standards apply, what zones of discharge are available, what monitoring is required, and what exemptions might be possible. Misidentifying the classification can lead to inadequate permit applications, compliance violations, and enforcement actions.

Section 2. Class F-I: Florida’s Most Protected Groundwater

2.1 Geographic Limits and Designation

Class F-I represents the pinnacle of groundwater protection in Florida, currently applying only to surficial aquifers in northeast Flagler County. The specific boundaries are precisely defined: the Atlantic Ocean forms the eastern boundary, the Intracoastal Waterway creates the western limit, the north line of Sections 8 and 39 in Township 10 South establishes the northern boundary, and a line running due east and west from the intersection with Fox’s Cut marks the southern extent.

This classification exists because the Commission determined this aquifer serves as the sole source of drinking water for the area’s population. The water quality is exceptional, with total dissolved solids less than 3,000 mg/L, making it suitable for consumption with minimal treatment. The combination of high quality, sole source status, and vulnerability to contamination justified creating Florida’s most stringent groundwater classification.

2.2 Standards and Requirements

Class F-I groundwater must meet all primary and secondary drinking water standards established under the Florida Safe Drinking Water Act. These include health-based standards for contaminants like arsenic, lead, and nitrates, as well as aesthetic standards for parameters like color, odor, and iron. Additionally, the minimum criteria prohibiting toxic substances apply throughout the aquifer.

What makes F-I protection exceptional is the virtual elimination of zones of discharge. Facilities must generally meet all standards at their point of discharge, with no dilution credit. Only domestic wastewater treatment plants and stormwater systems can receive minimal 100-foot zones, and only if they demonstrate protection of adjacent waters. Other facilities can obtain similar limited zones only by treating their discharge to near-drinking-water quality.

Section 3. Class G-I: Single Source Aquifer Protection

3.1 Designation Process

Class G-I applies to single source aquifers specifically designated by the Commission through formal rulemaking. Like F-I aquifers, these contain high-quality water with total dissolved solids less than 3,000 mg/L and serve as the only reasonably available potable water source for significant populations. However, G-I aquifers exist outside the specific Flagler County area designated as F-I.

The designation process requires extensive public participation. The Department must notify all affected local governments and legislators at least 60 days before public workshops. Prominent newspaper notices must appear in affected areas. The Commission must find that the aquifer truly represents the only reasonable water source and that designation is attainable considering all relevant factors.

3.2 Protection Standards

G-I aquifers receive nearly identical protection to F-I aquifers. They must meet all primary and secondary drinking water standards, with the same limited exceptions for coliform bacteria and asbestos. Zones of discharge are severely restricted, with only highly treated domestic wastewater and stormwater receiving automatic 100-foot zones.

The key difference from F-I lies in the treatment standards for non-domestic discharges seeking zones. While F-I requires treatment to standards in Rule 62-600.420(1)(c), G-I requires compliance with Rule 62-600.530. Both represent near-drinking-water quality, ensuring that even within limited zones, the discharge poses minimal risk to the aquifer.

Section 4. Class G-II: Standard Potable Water Protection

4.1 Default Classification

Class G-II serves as Florida’s default groundwater classification, applying to all aquifers with total dissolved solids less than 10,000 mg/L unless specifically reclassified. This encompasses the vast majority of Florida’s groundwater, including most of the Floridan Aquifer system that supplies drinking water to millions of residents.

The 10,000 mg/L threshold represents the upper limit of water that could reasonably be treated for drinking water use. While treatment becomes expensive as dissolved solids increase, technological advances continue to make higher-salinity waters economically feasible for potable use. The Commission therefore chose an inclusive approach, protecting all potentially potable water.

4.2 Applicable Standards

G-II groundwater must meet the same primary and secondary drinking water standards as G-I and F-I waters. The minimum criteria prohibiting toxic discharges apply throughout. However, G-II classification allows more operational flexibility through larger zones of discharge and broader exemption opportunities.

Within approved zones of discharge, only the minimum criteria apply, not the full drinking water standards. This recognizes that natural processes in soil and groundwater can treat many conventional pollutants if given adequate time and distance. The challenge lies in ensuring zones are properly sized to achieve treatment before groundwater reaches the zone boundary.

4.3 Special Provisions for Existing Installations

Facilities operating before the current regulatory framework receive important accommodations. Existing installations may be exempt from secondary drinking water standards outside their zones if the Department hasn’t made specific findings about threats to water supplies. They also maintain whatever zones their permits specify, or to their property boundaries if permits lack specificity.

These grandfather provisions recognize the unfairness of applying new standards retroactively to facilities that made investments based on previous requirements. However, the exemptions aren’t absolute. If monitoring shows threats to drinking water supplies or violations at water supply wells, the Department can revoke exemptions and require compliance.

Section 5. Class G-III: Non-Potable Unconfined Aquifers

5.1 Defining Characteristics

Class G-III encompasses two categories of non-potable groundwater in unconfined aquifers. The first includes naturally saline waters with total dissolved solids of 10,000 mg/L or greater. The second covers moderately saline waters between 3,000 and 10,000 mg/L that the Commission has determined have no reasonable potential as future drinking water sources.

The unconfined nature of G-III aquifers is significant. These waters exist without overlying impermeable layers, making them more susceptible to surface contamination but also more easily monitored and remediated if problems develop. Common G-III aquifers include shallow coastal aquifers affected by saltwater intrusion and inland aquifers with naturally high mineral content.

5.2 Limited Protection Standards

G-III aquifers must meet only the minimum criteria prohibiting toxic, carcinogenic, and acutely harmful substances. They need not meet drinking water standards since the water has no potable use. This limited protection recognizes that requiring drinking water quality in naturally contaminated aquifers would serve no purpose while imposing significant costs.

However, the minimum criteria still provide important protection. Facilities cannot discharge substances that would harm soil organisms needed for natural treatment. They cannot create nuisances or impair uses of adjacent waters. Most importantly, they cannot discharge toxins that might migrate to nearby G-II aquifers or connected surface waters.

5.3 Flexibility for Beneficial Use

The regulations provide significant flexibility for beneficial use of G-III aquifers. Deep injection wells can receive exemptions from even the minimum criteria if they obtain aquifer exemptions under the Underground Injection Control program. This allows disposal of treated wastewater into aquifers with no other beneficial use, provided adequate monitoring ensures waste remains contained.

Other facilities using G-III aquifers must still meet minimum criteria but enjoy simplified permitting and monitoring requirements. Zones of discharge are established case-by-case based on site-specific factors rather than rigid dimensional standards. This flexibility encourages beneficial use of marginal-quality waters while maintaining necessary environmental safeguards.

Section 6. Class G-IV: Deep Confined Non-Potable Aquifers

6.1 Characteristics and Occurrence

Class G-IV represents Florida’s least protected groundwater, encompassing confined aquifers with total dissolved solids of 10,000 mg/L or greater. These deep, highly saline formations exist beneath impermeable confining layers that prevent upward migration of contamination. The water often contains dissolved minerals at concentrations many times higher than seawater.

In Florida, G-IV aquifers typically occur at depths greater than 1,000 feet below land surface. The Boulder Zone in south Florida represents the most utilized G-IV aquifer, accepting millions of gallons daily of treated domestic and industrial wastewater. The natural water quality is so poor that additional contamination has negligible impact.

6.2 Case-by-Case Standards

Unlike other classifications with predetermined standards, the Department establishes G-IV requirements case-by-case. The minimum criteria don’t automatically apply unless the Department identifies specific dangers. This complete flexibility recognizes that protecting water with no beneficial use serves no purpose while potentially preventing beneficial disposal options.

Standards typically focus on ensuring waste remains within the receiving formation rather than protecting the formation itself. Monitoring emphasizes detecting upward migration through confining layers rather than changes in the receiving aquifer. Permits may allow discharge of substances that would be prohibited in other aquifers, provided confinement is assured.

Section 7. The Reclassification Process

7.1 Who Can Seek Reclassification

Any substantially affected person or water management district may petition for groundwater reclassification. The Department itself may initiate reclassification through rulemaking. This open process ensures that classification decisions can be revisited as new information becomes available or circumstances change.

Petitions must be filed with the Department’s agency clerk in the Office of General Counsel in Tallahassee. While no specific fee applies to reclassification petitions, petitioners should expect significant costs for technical studies supporting their request. The petition must contain sufficient information to support all required findings.

7.2 Required Findings

The Commission can only reclassify groundwater upon three affirmative findings. First, the proposed reclassification must establish the present and future most beneficial use of the groundwater. This requires showing that the current classification either overprotects or underprotects the resource relative to its actual use potential.

Second, reclassification must be clearly in the public interest. This goes beyond benefiting the petitioner to demonstrating broader community benefits. Economic development, water resource conservation, and environmental protection all factor into public interest determinations.

Third, the proposed designated use must be attainable considering environmental, water quality, technological, social, economic, and institutional factors. The Commission won’t adopt aspirational classifications that can’t be realistically achieved and maintained.

7.3 Additional Requirements for Single Source Designations

Upgrading aquifers to G-I or F-I status requires meeting additional stringent requirements. Beyond the standard three findings, the Commission must determine that the aquifer represents the only reasonably available potable water source for a significant population segment.

This determination requires extensive analysis. The Commission considers alternative water sources and their development costs. Long-term adequacy of the aquifer to meet future demands receives careful scrutiny. Potential health effects if protection doesn’t occur must be weighed against impacts on existing dischargers if protection is granted. The process ensures that single source designations are reserved for truly critical water resources.

Section 8. Implementing Water Quality Standards

8.1 Primary Standards Application

All Class F-I, G-I, and G-II groundwaters must meet primary drinking water standards established under the Florida Safe Drinking Water Act. These health-based standards set maximum allowable concentrations for contaminants that pose risks to human health. The standards apply throughout the aquifer, except within approved zones of discharge where only minimum criteria apply.

Primary standards cover approximately 90 different contaminants including microorganisms, disinfection byproducts, inorganic chemicals, organic chemicals, and radionuclides. Maximum contaminant levels are set based on health risk assessments assuming lifetime consumption of two liters per day. This protective approach ensures groundwater remains safe even for the most vulnerable populations.

8.2 Secondary Standards Requirements

Secondary drinking water standards address aesthetic concerns rather than health risks. Parameters like iron, manganese, and sulfates affect water’s taste, odor, or appearance but don’t pose health hazards at regulated levels. F-I, G-I, and G-II waters must meet these standards to ensure the water remains palatable and acceptable to consumers.

However, significant exemptions exist for existing installations in G-II aquifers. These older facilities need not meet secondary standards outside their zones unless the Department makes specific findings about impacts on water supplies. This pragmatic approach recognizes that requiring aesthetic improvements at older facilities may provide minimal benefit at significant cost.

8.3 Natural Background Exceptions

When groundwater naturally exceeds drinking water standards, the natural background concentration becomes the applicable standard. This provision recognizes the impossibility and pointlessness of requiring water quality better than natural conditions. It applies to both primary and secondary standards, including pH when natural levels fall outside acceptable ranges.

Determining natural background requires careful investigation. Historical data from before human impacts provides the best evidence. Regional studies showing consistent elevated levels across unimpacted areas support natural background claims. The burden lies with dischargers to demonstrate that exceedances reflect natural conditions rather than contamination.

Section 9. Minimum Criteria: The Universal Foundation

9.1 Absolute Prohibitions

Regardless of classification, all groundwater must remain free from certain harmful discharges. These minimum criteria apply even in G-IV aquifers unless the Department specifically determines no danger exists. They represent the absolute floor below which water quality cannot fall.

The prohibitions protect both human health and ecological integrity. Discharges cannot harm soil organisms essential for natural treatment processes. Carcinogenic, mutagenic, teratogenic, or toxic substances face prohibition unless specific numerical standards exist. Acute toxicity in connected surface waters triggers violations even if groundwater organisms survive.

9.2 Nuisance and Use Protection

Beyond health and ecological concerns, minimum criteria protect quality of life and property rights. Discharges cannot create nuisances that unreasonably interfere with neighbors’ property enjoyment. They cannot impair reasonable and beneficial uses of adjacent waters, whether groundwater or surface water.

These provisions provide important protections in disputes between neighbors. A facility meeting all numerical standards still violates minimum criteria if odors, unsightliness, or other impacts constitute a nuisance. Similarly, even G-III discharges cannot prevent neighbors from using their groundwater for irrigation or other non-potable purposes.

9.3 Implementation Through Case-by-Case Determinations

The Secretary possesses exclusive authority to determine specific concentrations that violate minimum criteria for toxic substances lacking numerical standards. This authority cannot be delegated to district offices, ensuring statewide consistency in these critical determinations.

The process includes extensive procedural safeguards. Proposed determinations require publication in the Florida Administrative Register. The Department must report all determinations to the Commission semiannually. Upon request, determinations must go through formal rulemaking. These procedures balance the need for quick response to emerging contaminants with due process protections.

Section 10. Practical Applications and Compliance Strategies

10.1 Determining Site Classification

The first step in any groundwater discharge project involves determining which classification applies. This requires more than simply checking a map. While the Department maintains GIS layers showing approximate classifications, site-specific investigation often reveals complexities.

Start with desktop review using Department resources, water management district data, and USGS publications. Examine nearby well construction reports for water quality data. Review regional hydrogeologic studies for aquifer characteristics. However, recognize that boundaries between classifications rarely follow neat lines and may vary with depth.

10.2 Confirming Classification Through Investigation

Desktop review should be followed by site-specific investigation. Install temporary monitoring points or borings to collect water quality samples. Analyze for total dissolved solids and other indicators of water quality. In areas near classification boundaries, multiple sampling points at different depths may be necessary.

Document findings thoroughly, as classification disputes can derail projects. If results indicate a different classification than regional mapping suggests, consult with Department staff early. They may require additional investigation or accept your findings based on data quality and representativeness.

10.3 Planning for Compliance

Once classification is confirmed, develop compliance strategies appropriate to the applicable standards. For F-I and G-I aquifers, this typically means advanced treatment systems capable of producing near-drinking-water quality effluent. For G-II aquifers, conventional treatment combined with appropriately sized zones of discharge often suffices.

Consider operational flexibility needs when designing systems. Standards tend to become more stringent over time, not less. Building in treatment capacity beyond current requirements provides insurance against future regulatory changes. Similarly, designing monitoring systems to exceed minimum requirements helps demonstrate responsible operation and may support future permit modifications.

Section 11. Economic and Practical Considerations

11.1 Cost Implications by Classification

The groundwater classification dramatically affects project costs. Discharging to F-I or G-I aquifers may require reverse osmosis or equally advanced treatment, with capital costs in millions and substantial operating expenses. G-II discharges typically need conventional biological treatment with costs an order of magnitude lower. G-III and G-IV discharges may require only basic pretreatment.

Beyond treatment costs, classification affects monitoring expenses. Higher classifications require more parameters, more frequent sampling, and more wells. Analytical costs for full drinking water parameters can reach thousands of dollars per event. Over a facility’s operational life, monitoring costs can equal or exceed treatment costs.

11.2 Site Selection Strategies

For new facilities with discharge needs, groundwater classification should factor prominently in site selection. The cost differential between classifications often exceeds land price differences between locations. A site over G-III groundwater may justify significantly higher land costs compared to a G-II location.

However, consider long-term reclassification potential. Areas experiencing saltwater intrusion may transition from G-II to G-III, providing operational relief. Conversely, improved water treatment technologies may lead to reclassification of marginal G-III waters to G-II status. Review regional water supply plans and growth projections when evaluating long-term classification stability.

11.3 Operational Flexibility Provisions

Each classification offers different operational flexibility. G-II facilities can request expanded zones of discharge by demonstrating protection of water resources. G-III and G-IV facilities enjoy case-by-case standard setting. Even F-I and G-I facilities can seek exemptions through the variance process, though at considerable cost and difficulty.

Understanding available flexibility helps optimize compliance strategies. Rather than installing treatment for parameters naturally present in groundwater, demonstrating natural background may provide relief. Instead of meeting secondary standards that provide no benefit, existing G-II facilities may qualify for automatic exemptions. These provisions require careful documentation but can substantially reduce compliance costs.

Section 12. Future Trends and Considerations

12.1 Emerging Contaminants

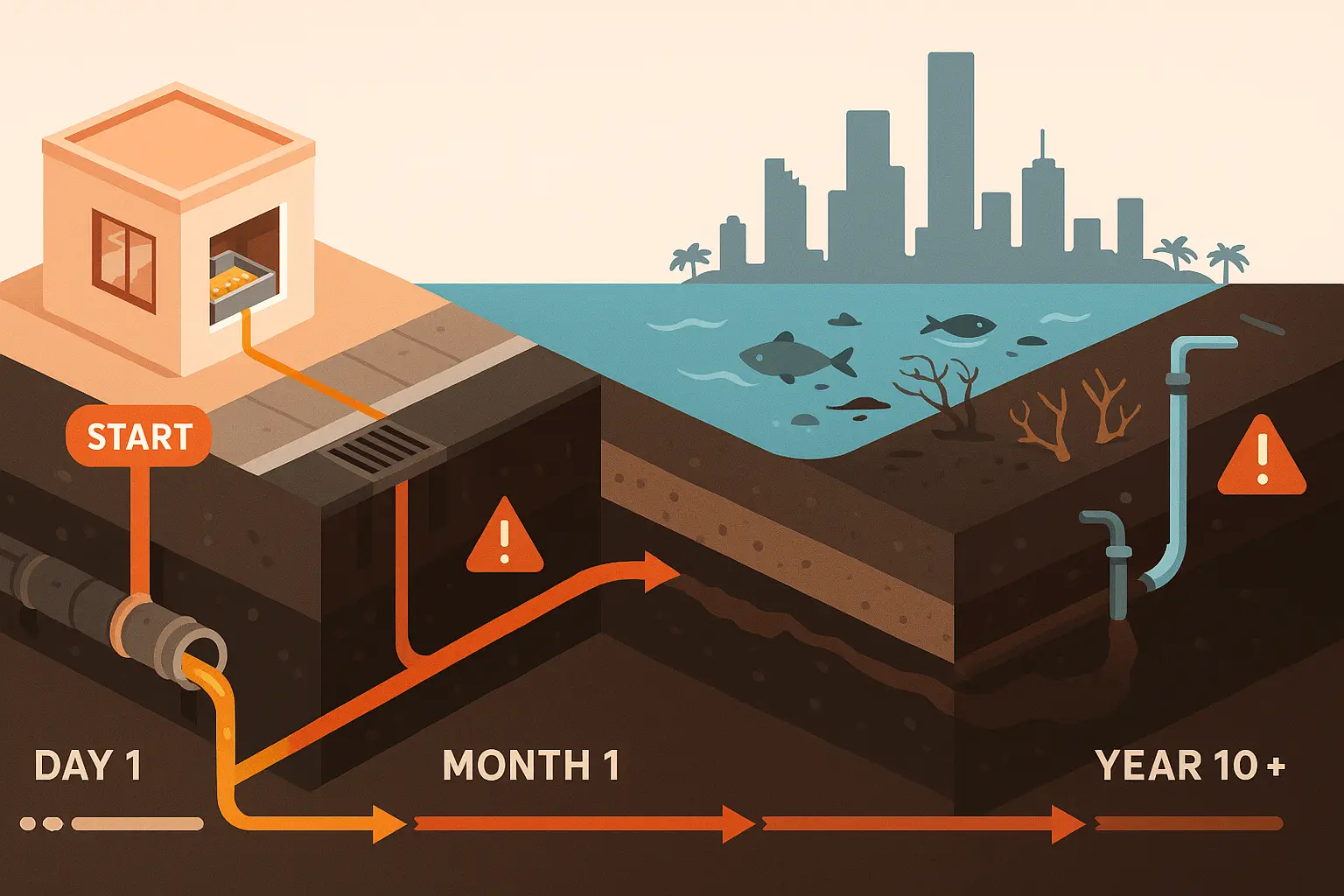

The groundwater classification system must adapt to emerging contaminant concerns. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), pharmaceuticals, and endocrine disruptors challenge traditional treatment approaches. As analytical methods improve and health effects research advances, expect new standards affecting all classifications.

Facilities should anticipate these changes through proactive measures. Installing flexible treatment systems capable of adaptation reduces future retrofit costs. Implementing source control programs prevents emerging contaminants from entering waste streams. Participating in research programs demonstrates environmental leadership while gaining early insight into regulatory trends.

12.2 Climate Change Impacts

Climate change increasingly affects groundwater classifications through multiple mechanisms. Sea level rise accelerates saltwater intrusion, potentially converting G-II aquifers to G-III status. Altered rainfall patterns affect aquifer recharge and natural background quality. Increased storm intensity challenges stormwater system designs based on historical patterns.

Adaptation strategies should consider these trends. Coastal facilities should evaluate saltwater intrusion projections when planning long-term investments. Interior facilities should assess drought vulnerability and aquifer sustainability. All facilities benefit from climate resilience planning that considers both physical and regulatory changes.

12.3 Technological Advances

Improving treatment technologies continue expanding options for meeting stringent standards. Membrane bioreactors provide superior biological treatment in compact footprints. Advanced oxidation processes destroy recalcitrant organics. Ion exchange and improved membranes reduce treatment costs for high-salinity waters.

These advances may support future reclassifications as previously unusable waters become economically treatable. They also provide existing facilities with upgrade options that may prove more cost-effective than seeking exemptions or relocating. Staying current with technological developments helps identify opportunities for operational improvements.

Section 13. Conclusion

Florida’s groundwater classification system represents a sophisticated approach to protecting diverse water resources while allowing beneficial use. The five-tier system from F-I to G-IV provides appropriate protection levels based on water quality and use potential. Understanding which classification applies to your site and what standards that classification imposes forms the foundation of regulatory compliance.

Success requires more than simply meeting numerical standards. It demands understanding the philosophy behind classifications, anticipating how standards may evolve, and implementing strategies that provide operational flexibility while protecting water resources. Whether discharging to pristine F-I aquifers or deep G-IV formations, the classification system provides a framework for responsible water resource management.

As Florida continues growing and water resources face increasing pressure, the classification system will undoubtedly evolve. Facilities that understand not just current requirements but underlying principles position themselves for long-term success. By embracing the protective intent while utilizing available flexibility provisions, dischargers can achieve compliance while maintaining operational efficiency.